A timely read to consider for our program with Dr. Achuta Kadambi.

“We Teach A.I. Systems Everything, Including Our Biases”

The future is in wastewater! Upcoming ALOUD on Science guest Dr. William Tarpeh reimagines water conservation. Read up on this trailblazing science.

How is California’s favorite burger impacting the environment? Get familiar with soon-to-be ALOUD on Science moderator Deborah Netburn’s work.

Check out this interview with LA Time’s science and medicine editor, Karen Kaplan, who will be featured in the new ALOUD on Science series’ first program!

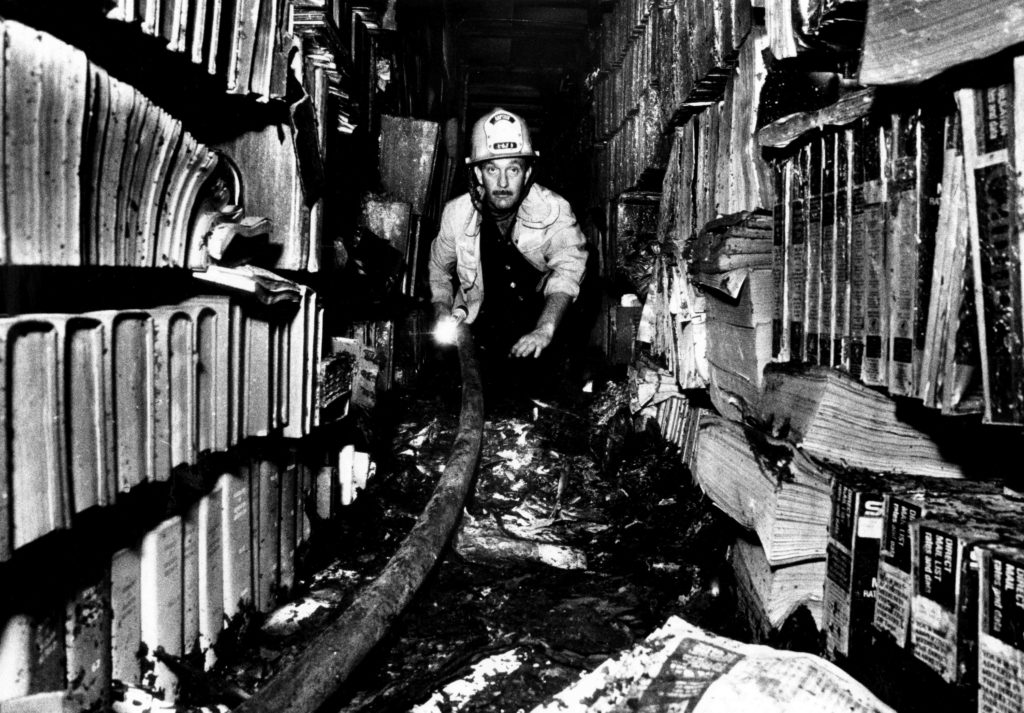

“The library is a gathering pool of narratives and of the people who come to find them. It is where we can glimpse immortality; in the library, we can live forever,” writes Susan Orlean in her newest work, The Library Book. The New Yorker staff writer and author of seven books, including Rin Tin Tin and The Orchid Thief, dives into the ashes of the catastrophic 1986 fire that burned down Los Angeles’ beloved Central Library, destroyed or damaged more than one million books, and shook our city to its core. Likely arson, but never fully solved, Orlean reopens the mysterious case to investigate if someone purposefully set fire to the Library. Through meticulous research, Orlean’s story grows into a rich cultural history of Central Library—and libraries across the world. We spoke with Orlean before she brings this story of persistence home to the Central Library for a special conversation and launch of her book at ALOUD on October 16.

Your own personal story of trips to the Shaker Heights Public Library in Ohio with your mother is one of the entrances into The Library Book. Were these childhood memories something that you always wanted to write about and how did this influence the overall story of your book?

Orlean: Those memories were lurking, but I hadn’t realized how powerful they were and how much I wanted to describe them until I visited the Studio City Branch Library with my son. In that moment, I was so overwhelmed by memories of visiting the library with my mother that I felt compelled to write about it. The motif of those visits colored the entire book. The transmission of stories—passing them from one person to the next, and making sure they are preserved—is at the heart of what a library does, and, as I realized, it’s at the heart of the relationship between parent and child.

You really immersed yourself into the history of Los Angeles and its library system in order to investigate the mystery of the fire. As an “outsider” journalist, how were you able to gain access into this story?

Orlean: I approached the story as an explorer, a student, eager to learn everything I could. I spent many, many days just roaming around the library, taking it in, and many more days in each department, sitting with some of the staff and trying to learn what they do and how they do it. Then I dug through a score of boxes of archival material about the Library’s history; those were an incredible resource, and made me feel like I was able to piece together the story of how the place had developed.

What were some of the biggest discoveries or surprises along the way?

Orlean: The difficulty of investigating arson shocked me; I had no idea how few arsons are solved and successfully prosecuted. But what surprised me the most was the story of Harry Peak [the main suspect] and his fumbling, contradictory, maddening inconsistency. I had trouble imagining how someone could be his or her own worst enemy, walking straight into self-incrimination. The astonishing range of human behavior is always the most surprising part of any story.

The book includes such an interesting cast of characters—including Mary Foy, an 18-year-old woman who was named as the head of the Los Angeles Public Library in the male-dominated era of the late 1800’s. How do you think having such progressive leadership early on changed the fate of our Library?

Orlean: LAPL has always been among the most progressive, public-minded libraries in the country. That emerged from its early leadership as well as its structure as a city department. The Los Angeles City Librarians have been exceptionally strong, independent individuals—you couldn’t get stronger and more independent than, say, Mary Jones, who ran the library at the turn of the century and led the way to modernize the place, or Charles Lummis, the explorer/scholar/writer/historian/eccentric who took over in 1905 and left an indelible mark (including using cattle brands on books to discourage petty theft)! And unlike some older libraries that were dominated by their early, wealthy, conservative founders, the library in Los Angeles had egalitarian roots, and that spirit has continued to this day.

The book turns from the past to consider the modern era of libraries. Since writing this book, what has changed about your perspective of the vital role that libraries have in our society today?

Orlean: I came to see libraries as much more than the repositories of printed material. In this era, they are centers of knowledge and information—a broader definition that includes the various means of sharing information (digital, streaming, as well as physical manuscripts), but also the sharing of information one-to-one, such as literacy programming and voter registration. Playgrounds and parks are the community spaces for our physical needs; libraries are the community spaces for our intellectual needs. Libraries will continue to adapt to provide what those needs are and the forms they take, and that’s what will keep libraries relevant and essential, and why they will endure.

Susan Orlean

The Library Book

Tuesday, October 16, 7:30PM

In conversation with author and Library Foundation Board Member Attica Locke

At its core, the public library is an enthusiastic collector: a repository of books, a keeper of history, a holder of information, a gathering place for all. Libraries collect to advance and share knowledge, and to strengthen communities through a vast compilation of resources. For the first time in its long history of collecting, the Los Angeles Public Library in a partnership with the Library Foundation presents a new exhibition that explores the inherent power of collections.

21 Collections: Every Object Has a Story will run from September 28 through January 27 at the Central Library’s Getty Gallery, showcasing a diverse range of historic, contemporary, and newly commissioned original collections. By bringing together vastly eclectic collections into a singular space and shining a light on the varying approaches and aesthetics of amassing objects, the exhibition reconsiders the act—and art—of collecting. “We began by asking what unique and compelling stories might be revealed through a collection that wouldn’t be possible if someone hadn’t brought it together. In the context of related things, or through a repetition of like elements, objects begin to give form to narratives, revealing sometimes surprising connections,” says 21 Collections Curator Todd Lerew. “The best collections are the ones that help us understand something about ourselves and our world.”

Audiences have the chance to take in collections of history, sociology, culture, and personal ephemera that represent untraditional perspectives on what warrants our attention. What might looking at a series of anonymous vintage photographs of men standing in rows say about the emotional undercurrent of 21st century masculinity? What does an obsession with paper airplanes comprised from scraps of political flyers, beer bottle labels, and children’s homework say about the commonalities of strangers?

“The wonderfully diverse, eclectic group of stories presented in this exhibition–and the collectors responsible for them–add up to an inspiring and surprising portrait of the value of collecting,” says City Librarian John F. Szabo. “Preserving the collections that tell the stories of our communities is at the core of the mission of the public library, where we have the unique responsibility of making those stories accessible to absolutely everyone.”

Below are a few highlights from 21 Collections. Visit lfla.org/21collections to learn more about this upcoming exhibition and related public programming across the city.

Prison Landscapes

Flipping through a family photo album, artist Alyse Emdur discovered a photo of herself at age five in front of a tropical backdrop. Remembering the photo was from a trip to visit her brother in prison, she became interested in these idyllic scenes that inmates often posed in front of depicting “fantasy” worlds of freedom. She started writing to inmates across the country requesting information about these backdrops, their own photos, and stories from their incarcerated lives. This community-generated project grew into a collection over 100 powerful images offering a glimpse of the surreal life from inside prison.

Bird Eggs and Nests

The Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology (WFVZ) is home to the world’s largest collection of bird eggs and nests. In the mid-20th Century, mainstream institutions like the LA County Natural History Museum were deaccessioning their egg collections, thinking they had been comprehensively studied and documented. When the DDT scare hit in the 1960s, the WFVZ was the only institution with enough specimens gathered prior to the pesticide’s invention to prove it was affecting the thickness of the egg-shells and threatening key species. Evidence from their collection was used in the court case that ultimately saw DDT banned by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Bullfighting Collection

One of the Los Angeles Public Library’s most unique research holdings, the Biblioteca Taurina or Bullfighting Collection, was compiled by LAUSD Spanish teacher George B. Smith in his Westlake apartment, and is the largest of its kind in North America. Although bullfighting is now a controversial (and illegal) activity, it was once common at Spanish religious festivals in Los Angeles, and the Portuguese (bloodless) version actually still takes place throughout the region to this day.

The Candy Wrapper Museum

Growing up in Southern California in the 1960s, Darlene Lacey wanted to start a collection, and candy was all that she could afford. She started with “Nice Mice,” because she liked the design and guessed it might not be around forever. Her collection, now dubbed the Candy Wrapper Museum, has since grown into one of the most significant collections of its kind, providing a window into cultural trends and fads, the history of graphic design and advertising, as well as a powerful nostalgia trip for all but the very young.

21 Collections: Every Object Has a Story

September 28 – January 27, 2019

Getty Gallery, Central Library

Photos Credit: Ian Byers-Gamber

Jonathan Gold contributed this essay about Saint Estèphe for the book To Live and Dine in L.A.: Menus and the Making of the Modern City. The book was part of the special exhibition “To Live and Dine in L.A.” that was hosted at Central Library in 2015.

If you had visited Saint Estèphe in the mid-1980s, a bleached-white dining room near a Coco’s in a Manhattan Beach mall, you probably ordered the chile relleno with goat cheese, the restaurant’s most famous dish. This was a different L.A. then, with Depeche Mode on the radio and Less Than Zero on the best-sellers list; the internationalist good vibes and the turquoise-magenta palette from the 1984 Olympics just beginning to fade. Spago was the dominant restaurant not just in Los Angeles but in the United States then, and casual, highly flavored Spago-style grill cuisine was in its ascendency.

But Saint Estèphe, you could tell in an instant, was something else entirely. That chile relleno, for example, was listed on the menu as “chile relleno, farci avec une duxelle et servi avec un sauce de chevre et d’ail,’’ and the crispness of both the service and the dining room also hewed to the original French. The roasted, peeled chile, when it came, was in the precise center of a very large plate, atop a pillow of cream sauce flavored with Laura Chenel’s fresh goat cheese from Sonoma, which was as ubiquitous in a certain kind of restaurant then as uni is now, and stuffed with duxelles, a rich preparation of minced mushrooms cooked down in butter that has been a part of haute cuisine since at least the time of La Varenne. This was not smoky, crisp, herbaceous California cuisine; this was classic French cooking with New World ingredients, and in fact the same duxelles had stuffed a steamed chicken breast at Saint Estèphe just a few years before when the restaurant was purely French. It was the birth of something, but of what it was hard to tell.

John Sedlar, who is chef at Rivera now, and who was the young auteur of Saint Estèphe then, is one of the most innovative chefs ever to wield a whisk in Los Angeles, a veteran of Jean Bertranou’s great La Cienega French restaurant L’Ermitage who created the institution of Modern Southwestern Cuisine at Saint Estèphe out of classical technique and the earthy ingredients he’d grown up eating as a boy in Abiquiu, New Mexico, not far from the studio of Georgia O’Keeffe.

The first blue-corn tortilla chip came out of Saint Estèphe, as a single, crunchy star served as an amuse-bouche of three corn kernels and a swirly stripe of chile puree, and Sedlar may also have been the first French-trained chef to play with chile-rubbed meat. He arranged American caviar, which was then considered vulgar, into abstracted rattlesnakes or into fierce-eyed kachina heads, like something out of a Hopi weaving. He raised the then-new art of plate-painting to new, squirt bottle–driven heights. (The Painted Desert salmon was plated on something like a Frederic Remington sunset drawn entirely in flavored sauce.)

Twenty-five years later, when Sedlar served the 1986 Saint Estèphe menu at his downtown restaurant Rivera, it was a fascinating look at the food at an important moment in Los Angeles culinary history, like a set by Led Zeppelin tucked into the context of a Robert Plant show. That chile relleno, that interplay between the goat cheese and suave chile heat, the impossible butterfat bomb of the cream sauce and the duxelles, was as precise an evocation of a specific historical moment as anything I’ve ever encountered: an old menu made flesh.

Saint Estèphe had been a restaurant in a constant state of evolution, from classic nouvelle cuisine to what it had become by 1986 or so: still a French restaurant but transformed, so that the squab was served with a buttery puree of pinto beans instead of sorrel sauce; the red-wine sauce with the duck breast, formerly in the style of Bertranou, was spiked with hominy; and the jus on the saddle of lamb was amped up with tiny, spicy chiles piquins. In just a couple of years, the sauteed sweetbreads in the style of the Parisian chef Alain Dutournier, with turnips, pistachios and orange zest, had become sweetbreads with chile con queso, the favorite guilty pleasure of every Tex-Mex aficionado, although I suspect that Sedlar’s version contained neither Velveeta nor Ro-Tel tomatoes.

But as the Don Quixote written by a 20th-century Frenchman in the Borges story was not the Don Quixote written by the 16th-century Cervantes – in the context of Rivera, Saint Estèphe became something radically different. In the 1980s, diners may have recognized a dish of eggs scrambled with goat cheese, cream and jalapenos, then put back in their shells, as a Southwest challenge to the nouvelle cuisine standard of soft-scrambled eggs with caviar. Twenty-five years later, the preparation read as nostalgic comfort food.

A plate of ravioli stuffed with carne adobada, a dish that had worked its way through the Cheesecake Factories of the world by the end of the Reagan administration, was less revolutionary than it was delicious. I loved that Painted Desert salmon, and the frieze of squirted cream sauces that framed the small piece of steamed fish — I once compared the pattern to an EKG chart — and Sedlar’s seared-scallop nachos with Roquefort. The slouchy blue-corn crepes were exactly as I remembered, down to the half-melted scoop of pumpkin ice cream. The prices on the menu were even pretty much unchanged – we were spending a lot more for nice meals in the 1980s.

But could the same menu cooked by the same chef, with the same ingredients from the same farmers possibly be the same as it was in that Manhattan Beach dining room? Clearly, it could not.

“This is the story of the most important and emblematic environmental and public health disaster of this young century. More bluntly, it is the story of a government poisoning its own citizens, and then lying about it. It is a story about what happens when the very people responsible for keeping us safe care more about money and power than they care about us, or our children,” writes Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha in What the Eyes Don’t See: A Story of Crisis, Resistance, and Hope in an American City. Her new book is also a deeply personal story—the story of an immigrant, a pediatrician, a mother, and a concerned citizen who against all odds used science to prove the children of Flint, Michigan were being exposed to lead.

Named one of the 100 Most Influential People in the World by Time Magazine in 2016 and dubbed a “bad ass” by Rachel Maddow, Dr. Mona has testified twice before Congress about the Flint water crisis, penned a New York Times Op-Ed for federal assistance for Flint children, and led the way for $100 million in federal dollars and $250 million in state dollars being awarded to Flint to address the crisis. As she continues to fight for the children of Flint, we spoke to Dr. Mona about hope in a time of crisis before her upcoming visit to ALOUD on July 11.

Your book weaves together your personal background with political, environmental, and public health histories. How did all of these pieces congeal into the saga of the Flint water crisis?

Dr. Mona: This book has so many seemingly disconnected topics like a genocide in Iraq, a public health history, the labor history, Arabic words and food. But when I began to write the story, I could not pull them apart because it’s all part of the lens that I see the world and my work, and it offers a full picture of how I got into this fight. The personal story of how I was raised and growing up in the milieu where injustice was keenly known gave me heightened antenna to look out for injustice wherever I am—not just across the ocean but right here in our own backyard. People ask me why I did this. It was a choiceless choice. It was because of my upbringing and this set of values.

How did growing up Iraqi American and having family stories from the Iraqi genocide prepare you for standing up against corruption and a failing system?

Dr. Mona: I always thought of myself as different and an underdog, and every day I felt blessed to be where I was [growing up in Royal Oak, Michigan]. The American Dream so worked for my family and I was so lucky to be where I was—I could have been where my cousins were in Iraq with air raids and sanctions. It was having that lens of being so lucky and blessed and being grateful that has pushed my work and my career in service.

Today we hear a lot about the bad news coming out of Flint, but your book is a love story to this place. What drew you to Flint?

Dr. Mona: Flint is a place of extremes. At one point Flint had the highest per capita income in the country. It’s where manufacturing started and it’s where the middle class started. Now Flint has one of the highest poverty rates in the country. It’s also a place where a lot of our civil rights struggles happened. The greatest irony of Flint in terms of the water crisis is that we are literally in the middle of the Great Lakes—we are in the middle of the largest source of freshwater in the world. Twenty percent of the freshwater in the world is around us and yet, to this day, people don’t have safe drinking water. What drew me to Flint, what has kept me in the city, what wakes me up every morning is the incredible resilience of the people here who are tough and loyal. This crisis has brought people together and everything we are doing is a model for the nation.

A low point of your fight was when you acquired the data that children were suffering from increased levels of lead, but you were initially dismissed by state officials. How did that affect your faith in government?

Dr. Mona: I’ve always been a believer in government—especially in the role to protect public health, to fight injustices, and to get rid of inequality. We need programs to protect our most vulnerable people, and the protection of air and water is the government’s job. But I now know about these weak rules and regulations that have failed to follow science. It was a massive realization: we are not a society that values children and values public health; that has been a lesson for Flint that must be shared.

The public library’s mission is to provide free access to ideas and information. What role do you think public libraries play in times of crisis or in standing up to injustice?

Dr. Mona: Our public libraries are the places to have these discussions and discourse and to connect people—especially people who are not alike. A big part of the Flint story is how it was folks from different disciplines, from different walks of life who came together. Often we think we’re alone in our fights and that there’s nobody else who cares about the issues, but having discussions and being exposed and having meeting places lets you realize that other people care about the environment, or children’s rights, or voting rights, or mass incarceration, or whatever issue that a library can provide a venue for.

Learn more about this upcoming ALOUD program:

What the Eyes Don’t See: A Story of Crisis, Resistance, and Hope in an American City

Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha

In conversation with journalist Geoffrey Mohan, LA Times

Wednesday, July 11 7:30 PM

Mark Taper Auditorium–Central Library

“I think it’s useful to see the world not as things and people but as a series of approaches and options for ways to perceive them. Language is approximate—it is a complicated code,” writes Laurie Anderson. An icon of performance art and the indie-music world, Anderson has been inventing new approaches to perceiving the world for over 40 years. As a musician, performance artist, composer, fiction writer, and filmmaker, Anderson moves seamlessly between the fine arts, music, and all the new media in between. But regardless of the medium, Anderson’s storytelling has always been driven by language. Now in the first book of her full career to date, All The Things I Lost in the Flood, Anderson curates a comprehensive collection of her artwork—from an opera inspired by Moby Dick to installations addressing Guantanamo and the bombing of Baghdad—and offers an intimate understanding of her creative process.

This spring ALOUD presents two dynamic programs with Anderson: on April 19 at Central Library, Anderson will discuss with award-winning writer Maggie Nelson her new book that traverses four decades of making groundbreaking art, then on April 20 at The Wallis, she will perform her west coast debut of a one-woman show that will, she said, “bring a book to life.” Before the legendary artist visits ALOUD, we asked Anderson about how books, politics, and the passing of time have shaped her storytelling.

As an artist you’ve pushed the boundaries of so many forms and disciplines and media—from experimental performance art to inventing new musical instruments and technology—usually working at the edge of the avant-garde. Writing a book is more mainstream by comparison—what made you want to publish this collection?

Anderson: I love books and treasure them. And it’s been a long time since I tried to put one together. I wanted to see if I could make something that still sounded like talking even though it ended up as print. Getting the sound of the voice into writing has always been a challenge. Plus, I wanted to make it conversational—to provoke, to suggest, to make something that didn’t wrap things up too neatly.

A lot of your work is in the performance realm, and you often refer to it as work-in-progress that evolves over time and changes with each new iteration. However, once a book goes to print, it is considered done. Did this idea of reaching a more final stopping point affect your creative process?

Anderson: Yes, you hit on the biggest downside of books for me. But I’m familiar with that finality from making records, films, and exhibitions. With this book there are many days when I wake up and think: Whoa! Why didn’t I include that (idea/story/picture/you name it)?

The stories in your new collection span a lifetime of making art. How did you select which stories to include—what memories or moments did you gravitate towards that felt essential to tell?

Anderson: I tried to stick to stories and how they affected and were affected by images; and so I tended to leave out lyrics for the most part and music almost completely. Since I’m known more as a musician than a visual artist I enjoyed the challenge. Also, with music it’s almost always better to play it than to write about it.

You’ve created political work through different historic moments, and today we are facing incredible challenges with the divisive political climate in our country. Why is storytelling important to you in the context of politics?

Anderson: The minute that politicians realized the power of stories—the story machine went into hyper-drive. You can set that date recently, or as far back as the mid-twentieth century, or as far back as the Norse myths. The stories that are being created, disseminated, analyzed, and promoted to achieve political ends these days are completely fascinating to me. Who’s writing them and who they’re addressed to is as crucial as the content.

Since the ALOUD series is part of the Los Angeles Public Library, we’re always interested about literary influences. How did books or libraries help to shape you as an artist?

Anderson: Books are an essential part of my work—often appearing as the central subject matter of performances, songs, and visual work. The Bible, Moby Dick, Crime and Punishment, The Tibetan Book of the Dead—have all been jumping off places for my work.

Learn more about the following events below, or tune-in to the livestream on April 19!

Thursday, April 19, 7:30 PM

All The Things I Lost in the Flood

Laurie Anderson

In conversation with Maggie Nelson

Reservations: lfla.org/aloud

Friday, April 20, 7:30 PM– SOLD OUT

All the Things I Lost in the Flood:

Laurie Anderson in Performance

The Wallis

Co-presented by ALOUD

Tickets: thewallis.org/anderson