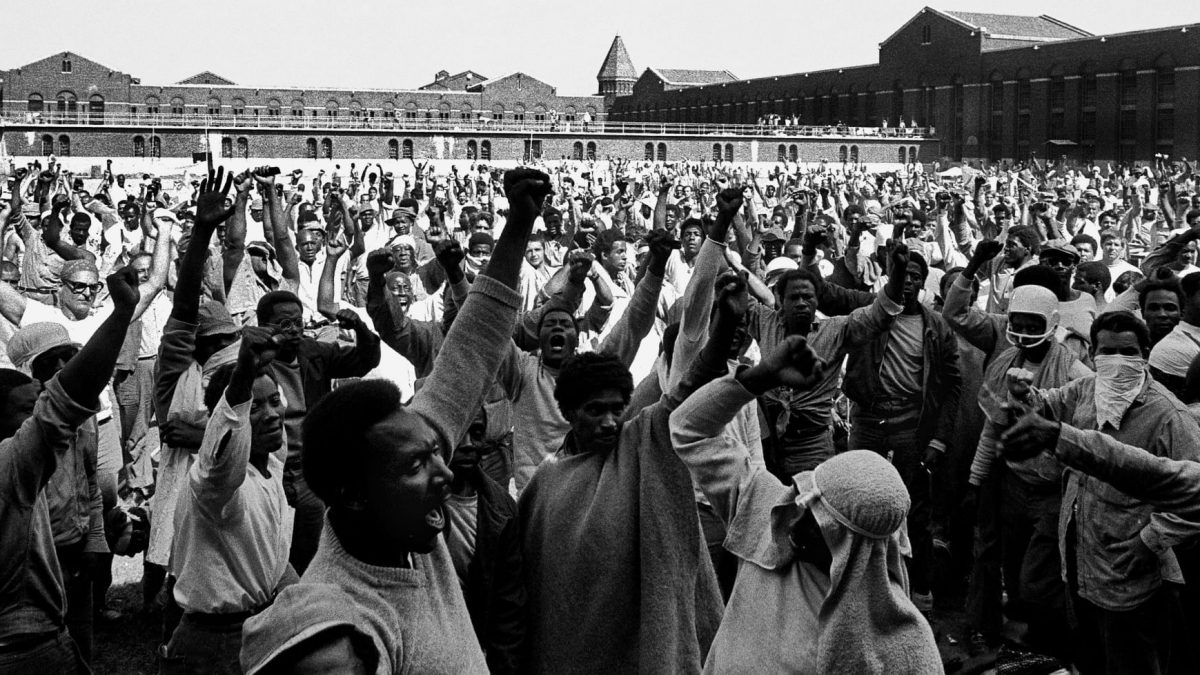

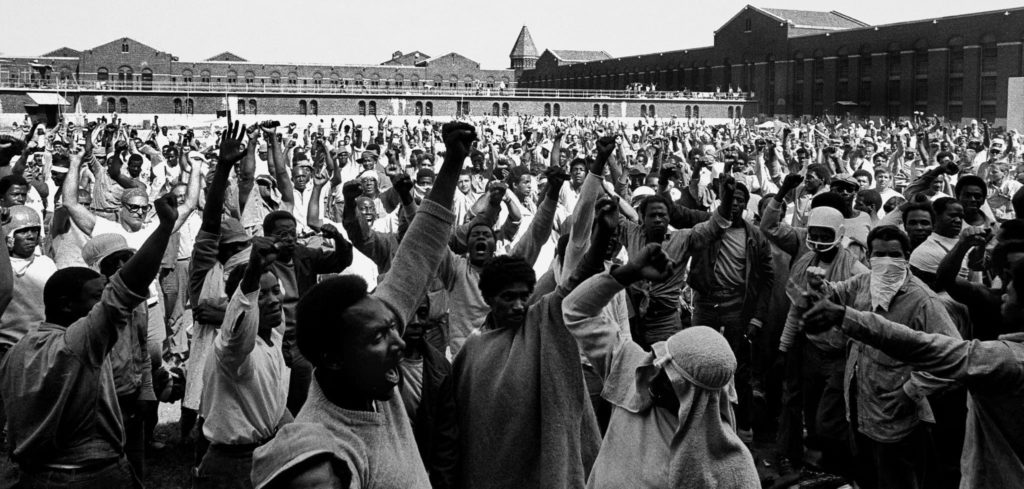

This January, the Los Angeles Public Library is paying tribute to the incredible legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr. through special programming across branch libraries from peace-themed craft projects for kids at the Benjamin Franklin Branch to exploring King’s life in books at the John Muir Branch. To shed light on another important story of the civil rights movement, ALOUD will welcome historian Heather Ann Thompson to the Central Library on Thursday, January 18. Thompson will share from her Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy, which chronicles the atrocities that led to 1,300 prisoners taking over the upstate New York correctional facility and how the state violently retook the prison—killing thirty-nine men and severely wounding more than a hundred others.

Her sweeping work explores the long-term implications of how this notorious prison riot was handled and offers new proof that the state of New York purposely concealed evidence and misrepresented the facts of the case to the public. Before Thompson takes the ALOUD stage, we spoke to her about the historic consequences of Attica’s narrative and what this tragedy can teach us about racial conflict, failures in mass incarceration, and police brutality in America today.

It’s always interesting to hear about an author’s research, but yours is especially important as the research itself became a crucial part of the story. Can you talk about this process?

Thompson: Virtually all of the files I wanted to see were either non-disclosable or had been moved to an off-site facility, and officially you could get them through the Freedom of Information Act, which I certainly tried to do, but the state [of New York] had absolutely no interest in providing public access to the story. I had to come at the story upside down, from the side, and backwards so that I could reconstruct what had happened. It was a journey that took me 13 years.

It was ultimately possible to tell the story from a combination of recreating an archive from disparate and unexpected sources, but also relying heavily on the survivors of Attica, as well as the judges, and lawyers, and reporters to share their stories with me. Ultimately, I could not have told the smoking gun parts of this story—I would not have known this was really a story of actual cover-up—had I not happened upon a whole cache of records [at the Erie County courthouse in Buffalo, New York] that I don’t think the state of New York knew was there.

Many individuals suffered tremendously from this cover-up, but what were the bigger historical consequences of this one falsely presented story?

Thompson: The micro answer is about the people who are most directly impacted by Attica. It destroyed lives quite literally. The macro cost of getting history wrong was devastating for all of us—for the nation. There was an entire generation of voters who in 1971 had been quite sympathetic to the idea of prison reforms. As a country we had turned against the death penalty and we had decided that prisons were too aggressive and brutal and large and we needed to think about community corrections.

Because we were told what had happened at Attica was that the prisoners had killed the hostages and that the prisoners had committed all of the harm—all of those horrific lies were printed on the front pages of The New York Times, The L.A. Times, over the AP and in every small town newspaper in America—the nation was sold a false bill of goods and became punitive. Politicians started using Attica as a symbolic way to get tougher on crime policy. Of course it turns out that the violence of Attica was because law enforcement was out of control, but we didn’t get that narrative and the national consequences have been devastating.

Recently at ALOUD, we’ve heard from other authors like Danielle Allen and James Foreman, Jr. who are also confronting the failures of the criminal justice system and the culture of secrecy around prisons. With more public discourse around these issues, do you think we’re at a tipping point for change?

Thompson: I am privileged to be part of this new wave of folks who are relentlessly and unapologetically talking about the fact that we have a crisis in our criminal justice system. Many people are working very hard to understand how we got here and to rally for something quite different and to suggest we don’t have to do it this way. We have a critical mass of people who are not going away—not just scholars—but we are being pushed and driven and informed by formerly incarcerated folks themselves. This is a crisis we know about because people on the inside are insisting we listen. For me, I feel hopeful, but I’m also deeply cautious because I know that we have zero transparency in our nation’s prisons.

It sounds like for you there’s a direct connection between transparency and change?

Thompson: Absolutely. The whole thrust of Blood in the Water is to say we need to look inside these institutions because the people inside of them—no matter what they did that got them there—they remain human beings. The story of Attica is fundamentally a story about humanizing the now more than 2.5 million people who are locked up in America or the 7.5 million under correctional control. It’s imperative to listen to prisoners.

Reservations: lfla.org/aloud

Thursday, January 18, 7:30 PM

Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy

Heather Ann Thompson

In conversation with Professor Kelly Lytle Hernandez,

Director of the Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies at UCLA

Save

Save