George Saunders—one of today’s most celebrated and influential writers—is beloved for his wildly imaginative short stories—little gems packed with walloping social criticism, philosophical quagmires, dark humor, and big heart. In his long-awaited first novel forthcoming this February, this short story master delivers his most original, transcendent, and moving work yet. Lincoln in the Bardo places the reader with Lincoln in a Georgetown cemetery on a rainy February night in 1862. From that seed of historical truth, the story spins into a metaphysical realm as a grief-stricken President Lincoln—one year into the Civil War—mourns the loss of his son Willie. Through a thrilling experimental form narrated by a chorus of voices and a cast of characters living and dead, Saunders grapples with the timeless question: How can we continue to love when everything we love must eventually be lost? Before Saunders joins ALOUD at The Writers Guild Theater for a special off-site program with author Anthony Marra on February 27, we spoke to Saunders about talking with ghosts, curating history, and the beauty of the Constitution.

The idea of a bardo—a form of purgatory in Tibetan Buddhism—is such an interesting and strange realm to place an American historical figure. How did these ideas of Western and Eastern worlds collide as you imagined this story?

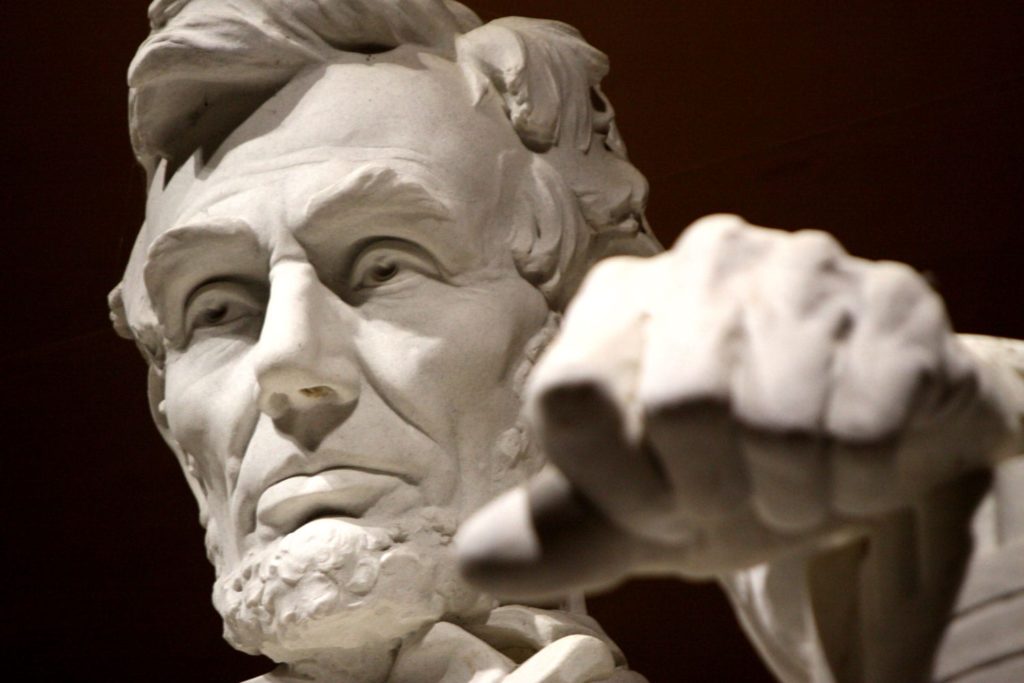

Saunders: The book takes place in a single night in a graveyard—my version of an event that was described in newspapers of the time, namely that Abraham Lincoln went, alone, to the crypt where his son, Willie, had recently been interred, to grieve and hold the body. That was an image that really captivated me, for many years. When I went to write it, though, I found I was in a sort of fix—Lincoln’s basically the only person in there, which makes an uphill slog for a novel—it’s all interior monologue, basically, and, uh, walking. So I thought: Who else could be in that graveyard at night? And I thought, of course: “Ghosts. Talking ghosts.”

And then I asked, well, why are they there? This put in my mind the term “bardo,” which is used in Tibetan Buddhism to mean “transitional space,” and is often used to refer to that transition between the moment of death and one’s subsequent rebirth. And I found that idea intriguing, that the graveyard might be populated with the spirits of these discontent beings, who are only marginally aware of where they were, and obsessed with what they had left behind or undone—so they can’t go on to whatever is next. In the Tibetan tradition, it’s said that in the bardo, a person will experience visions (negative or positive) based on his or her habits of mind. So that gave me a lot to work with and also made for some nice comedy: to find that these dead people were just like living ones (egotistical, self-obsessed, prideful, sweet, etc.). Except some can fly.

Since ALOUD takes place at the Los Angeles Public Library, we’re always curious about research. Can you describe your research into the Civil War era that influenced the narrative?

Saunders: I just tried to read everything I could about Lincoln and the period and especially about the death of Willie Lincoln, which is a very dramatic and sad affair. Then at one point I was struggling to get this knowledge into the book (without having some character wander in and declaim it) and I asked myself, “Well, how do YOU know all of this stuff?” And I hit on the idea of excerpting bits of the historical texts, and arranging them into chapters. That was a sort of crazy period—I typed up all the references and then cut them into pieces and was down on the floor rearranging them for maximum velocity, etc. It was really more “curating” than “writing,” but interestingly, some versions sucked and some were moving. I figured that might be one legitimate role for me in this book—to curate better, so to speak. So that was one form of research.

The other was that I knew I would have to “do” Lincoln’s voice, so I just immersed myself in his speeches, trusting that, when I had to speak in his voice, all of that reading would inform my attempts. I didn’t want to sound like his speeches (“Four score and fifteen minutes ago, I came into this graveyard”), especially since these were inner monologues (we think to ourselves in a different rhetorical mode than we speak publicly). So I tried to get his style into my head—and then just gave myself permission to riff, basically.

Although the story is based on history, you also deviate from the facts. What do you think blurring this line between the real and imagined adds to the characterization of President Lincoln?

Saunders: It occurred to me at one point that the way we read history is to take in the historical source, and then basically retell it to ourselves—imagine actions and ambience beyond what is literally depicted in the source. I had certainly done that with the historical texts I’d read over the years. So I gave myself permission to sort of “fill in the blanks”—to novelize the combined historical accounts so that they more closely matched the version in my mind, if you will. The intention was always heightened emotion.

After spending so much time imagining America in a time of war, has this changed the way you think about the present and our country in a time of war today?

Saunders: Well, at the risk of sounding corny, it made me love our country more and realize how tenuous it all is—our freedom and our civility and our traditions. Immersing myself in that period made me realize 1) that we almost lost our country once and 2) the things that were supposed to be established by victory back then (racial equality chief among them) are still not in place. That war was a struggle to align ourselves more closely with the very beautiful intention of the Constitution regarding true equality, and we didn’t get all the way there. I think Lincoln would be amazed and heartbroken to see that we still haven’t got it right, when so much was sacrificed.

Monday, February 27

The Writers Guild Theater

An Evening with George Saunders

Lincoln in the Bardo

In conversation with Anthony Marra

Tickets at lfla.org/aloud