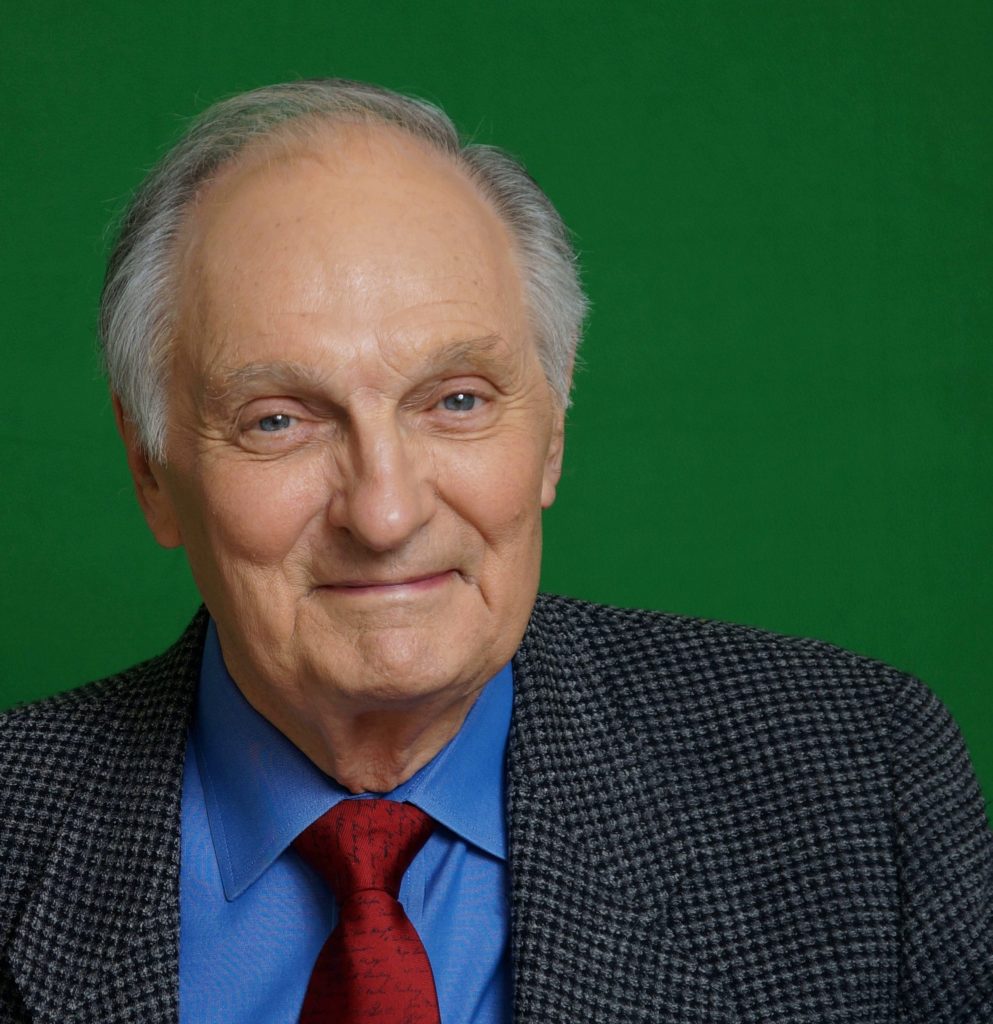

In 1993, Alan Alda, the award-winning actor and bestselling author, began hosting the PBS series Scientific American Frontiers. Although he was deeply fascinated by science, he initially struggled to interview the scientists and translate their complicated work to the masses. Digging into his arsenal of tools that he had honed as an actor and improviser to connect with audiences, he sharpened his communication skills for the PBS series—and for many other parts of his life. With his trademark humor and candor, Alda’s new book, If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look on My Face?, follows his decades-long quest to learn how to communicate better. Before Alda visits ALOUD on June 12 to share with audiences his strategies to build empathy and improve the way we talk to each other, we spoke to the communication guru about the science of storytelling.

Because of rapidly changing technologies, we’re constantly finding new ways to stay connected. Yet that doesn’t necessarily mean we are communicating better—is the timeliness of these issues of communication part of what compelled you to write this book?

Alda: I wrote it because I finally realized that I had learned something important over the last 20-25 years in helping scientists communicate, which is important for all kinds of communication—for all people, for all fields and not only at work, but at home between husbands and wives, and parents and children. But it actually goes back even further than those 20 years because I learned some of these things when I was a child as an actor. I grew up in a family where my father was an actor and I was on stage with him a lot and there were things I learned on stage about relating to another person.

A lot of the examples in your book that highlight these effective strategies for communicating involve art—like improv exercises. But then you turn to science to show us how they are effective—how they work in our brains. Where did your interest in science come from?

Alda: Just curiosity I guess. Ever since I was a little boy, I was very curious about things. When I was in my twenties I began reading an enormous amount of science just for entertainment because it was such a fascinating story to me—it’s like a detective story. You’re able to find out such amazing things on the basis of very little telltale clues.

It’s interesting to hear you call science a story because that’s not how most people think of the subject.

Alda: It is a story. I don’t think there’s an experiment or a life in science that isn’t a fascinating story. If you become familiar with telling stories and too often science and business proposals and people’s decisions on where the family should take their vacation—they’re not told as stories. You hear the conclusion first and you’re not involved. Storytelling is really involving and in the book there’s a part about how people with MRI machines have figured out that stories actually put you in sync with another person. Your brains are activated in very similar ways through stories.

Using stories to connect sounds like there’s a need for longer forms of communication, which is a little at odds in today’s world of technology and the popularity of short forms of communicating.

Alda: Some people actually try to tell stories with emojis, but I haven’t been able to figure out any of those stories yet. But the interesting thing about e-mail and social media messaging is that many more people are writing letters now than they did before they had their iPhones and computers. Some of them actually use whole sentences, which is rare, but they are communicating. With all this effort to communicate going on, keeping an eye on what is good communication is really important. You can get into very embarrassing situations with poor e-mailing. For example, you think you’re being funny, but it sounds sarcastic and antagonistic. But if you can keep in mind whom you are writing to and what they may be feeling and thinking, you actually run less of a risk for a verbal explosion.

This seems like an example of the importance of empathy, which you describe in your book as the core of good communication.

Alda: Yes, and I try to make it clear in the book that I don’t mean empathy which is often considered to mean that you are sympathetic with another person. You may or may not be sympathetic with another person—they may be holding a gun on you, but empathy would really help to know what they’re going through under the surface so you know how to respond to them better. As far as communication is concerned, empathy is a tool that really makes communication better, stronger, and more effective. It doesn’t necessarily turn you into a nice guy, but it helps if you want to be a nice guy.

Although your book is not trying to make any political statements, our country is very politically divided—and not being able to empathize with people from across the political divide is a huge impasse in reconciling our differences. Do you have any suggestions for how to talk politics with someone who shares very different views?

Alda: I’ve heard over and over of people who can’t talk to their families because they voted for different people. I think if you get into a shouting argument, the boat has already sailed. A really constructive exchange of opposing ideas is important—people shouldn’t all have the same ideas. The way to have a conversation instead of a shouting match is to as much as possible connect to the other person and to try to know what’s under their rant. If you can figure that out, then it often turns out that you both want the same thing, but you just have different strategies of getting it. Then maybe there’s a chance to discuss those different ways.

You’re taking part in the Library Foundation’s ALOUD series this June, which is one way the Los Angeles Public Library helps to engage the local community in conversation. How else do you see the public library as helping people to better understand each other?

Alda: I’ve always loved libraries and I think they are magical places. The idea of the library is so powerful because it’s about access to information. Libraries give us the chance to see a range of opinions and a range of perspectives.

Monday, June 12, 7:30 PM

The Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts

An Evening with Alan Alda

In conversation with Lisa Wolpe

Learn more about this program here.

Save

Save