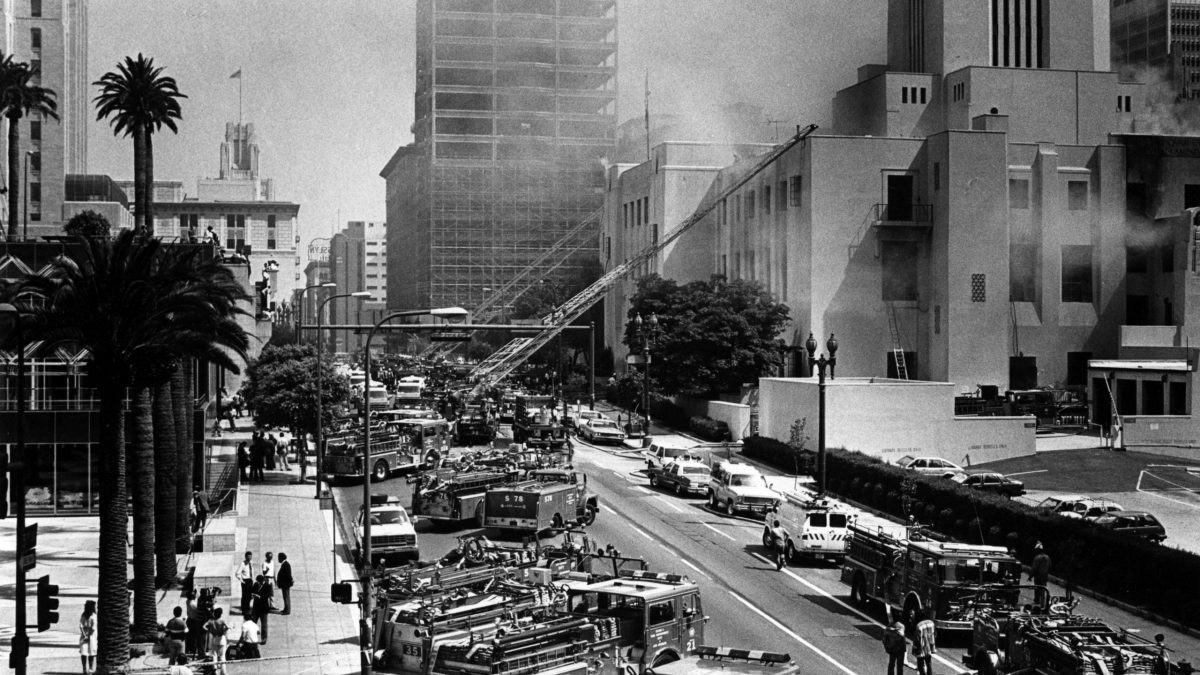

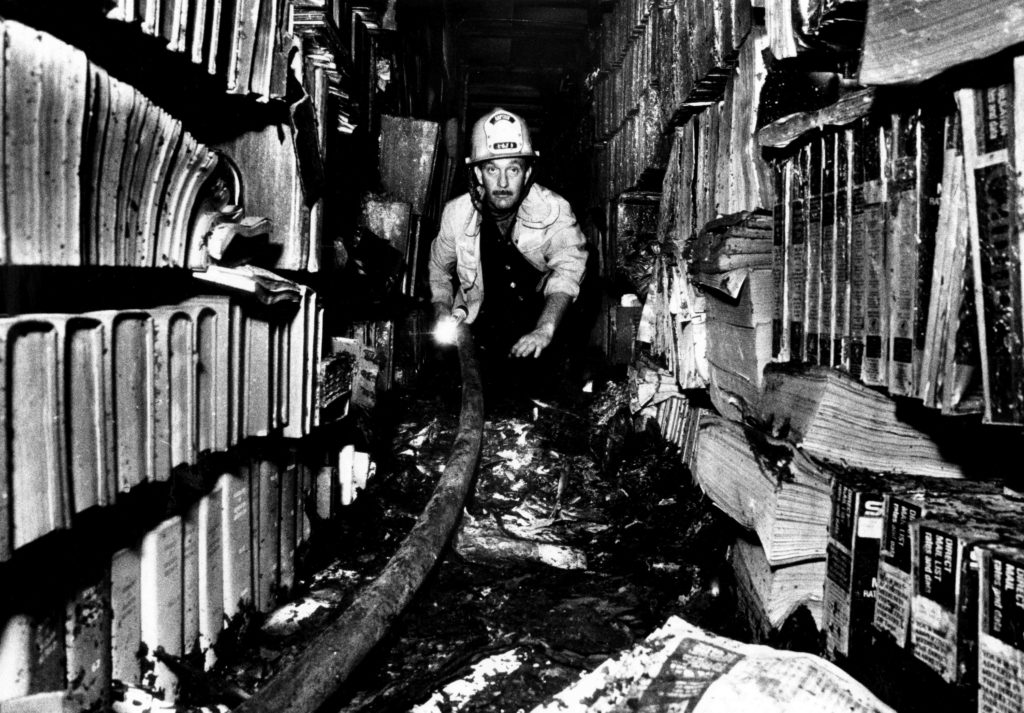

“The library is a gathering pool of narratives and of the people who come to find them. It is where we can glimpse immortality; in the library, we can live forever,” writes Susan Orlean in her newest work, The Library Book. The New Yorker staff writer and author of seven books, including Rin Tin Tin and The Orchid Thief, dives into the ashes of the catastrophic 1986 fire that burned down Los Angeles’ beloved Central Library, destroyed or damaged more than one million books, and shook our city to its core. Likely arson, but never fully solved, Orlean reopens the mysterious case to investigate if someone purposefully set fire to the Library. Through meticulous research, Orlean’s story grows into a rich cultural history of Central Library—and libraries across the world. We spoke with Orlean before she brings this story of persistence home to the Central Library for a special conversation and launch of her book at ALOUD on October 16.

Your own personal story of trips to the Shaker Heights Public Library in Ohio with your mother is one of the entrances into The Library Book. Were these childhood memories something that you always wanted to write about and how did this influence the overall story of your book?

Orlean: Those memories were lurking, but I hadn’t realized how powerful they were and how much I wanted to describe them until I visited the Studio City Branch Library with my son. In that moment, I was so overwhelmed by memories of visiting the library with my mother that I felt compelled to write about it. The motif of those visits colored the entire book. The transmission of stories—passing them from one person to the next, and making sure they are preserved—is at the heart of what a library does, and, as I realized, it’s at the heart of the relationship between parent and child.

You really immersed yourself into the history of Los Angeles and its library system in order to investigate the mystery of the fire. As an “outsider” journalist, how were you able to gain access into this story?

Orlean: I approached the story as an explorer, a student, eager to learn everything I could. I spent many, many days just roaming around the library, taking it in, and many more days in each department, sitting with some of the staff and trying to learn what they do and how they do it. Then I dug through a score of boxes of archival material about the Library’s history; those were an incredible resource, and made me feel like I was able to piece together the story of how the place had developed.

What were some of the biggest discoveries or surprises along the way?

Orlean: The difficulty of investigating arson shocked me; I had no idea how few arsons are solved and successfully prosecuted. But what surprised me the most was the story of Harry Peak [the main suspect] and his fumbling, contradictory, maddening inconsistency. I had trouble imagining how someone could be his or her own worst enemy, walking straight into self-incrimination. The astonishing range of human behavior is always the most surprising part of any story.

The book includes such an interesting cast of characters—including Mary Foy, an 18-year-old woman who was named as the head of the Los Angeles Public Library in the male-dominated era of the late 1800’s. How do you think having such progressive leadership early on changed the fate of our Library?

Orlean: LAPL has always been among the most progressive, public-minded libraries in the country. That emerged from its early leadership as well as its structure as a city department. The Los Angeles City Librarians have been exceptionally strong, independent individuals—you couldn’t get stronger and more independent than, say, Mary Jones, who ran the library at the turn of the century and led the way to modernize the place, or Charles Lummis, the explorer/scholar/writer/historian/eccentric who took over in 1905 and left an indelible mark (including using cattle brands on books to discourage petty theft)! And unlike some older libraries that were dominated by their early, wealthy, conservative founders, the library in Los Angeles had egalitarian roots, and that spirit has continued to this day.

The book turns from the past to consider the modern era of libraries. Since writing this book, what has changed about your perspective of the vital role that libraries have in our society today?

Orlean: I came to see libraries as much more than the repositories of printed material. In this era, they are centers of knowledge and information—a broader definition that includes the various means of sharing information (digital, streaming, as well as physical manuscripts), but also the sharing of information one-to-one, such as literacy programming and voter registration. Playgrounds and parks are the community spaces for our physical needs; libraries are the community spaces for our intellectual needs. Libraries will continue to adapt to provide what those needs are and the forms they take, and that’s what will keep libraries relevant and essential, and why they will endure.

Susan Orlean

The Library Book

Tuesday, October 16, 7:30PM

In conversation with author and Library Foundation Board Member Attica Locke

Save

Save